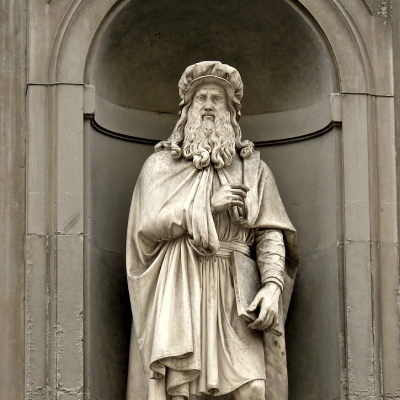

In the heart of Florence, beneath the arches of the Uffizi Gallery’s courtyard, stands a marble statue of one of history’s greatest minds—Leonardo da Vinci. This silent yet commanding figure is not merely a representation of the man, but a profound tribute to the genius who helped shape the Renaissance. Carved in the mid-19th century by the skilled Italian sculptor Luigi Pampaloni, the statue reflects both the timeless influence of Leonardo and the cultural pride of Tuscany. It is a visual ode to a man who defied the limits of any single discipline and whose name remains synonymous with human creativity, curiosity, and intellectual ambition.

The statue is part of a remarkable collection adorning the Uffizi’s exterior niches, each filled with sculptures of famous Tuscan figures. Commissioned under the patronage of Grand Duke Leopold II during a period of cultural revitalization in the mid-1800s, the project was designed to honor the memory and contributions of the region’s most outstanding thinkers, artists, and leaders. With Florence having served as the epicenter of the Renaissance, it was only fitting that these figures should be enshrined in the city’s architectural heart. Each statue in the series tells its own story, but the one of Leonardo da Vinci perhaps tells the most universal and enduring of all.

Luigi Pampaloni, born in 1791 in Florence, was already well-known for his elegant neoclassical sculptures when he was commissioned to create the likeness of Leonardo. He approached the subject not just as a sculptor, but as a thinker—seeking to capture the spirit of Leonardo rather than just his physical form. The resulting statue is one of great subtlety and grace. Leonardo is portrayed as an older man, with a long flowing beard and serene expression, wearing robes that identify him as a Renaissance thinker, an artist, and a man of contemplation. The drapery of the garments is masterfully carved, creating natural folds that suggest both movement and stillness—an equilibrium often associated with the neoclassical style.

In his left hand, Leonardo holds a closed notebook, a direct reference to the hundreds of manuscripts he left behind—filled with sketches, inventions, anatomical studies, philosophical thoughts, and scientific observations. These notebooks are among the most valuable documents of Renaissance thought, offering insights not only into the workings of Leonardo’s mind but also into the evolution of knowledge itself. The positioning of the notebook close to his body suggests the deeply personal nature of his studies. It is not merely a prop, but a symbol of the inner world from which Leonardo drew his brilliance.

His right hand is raised to his chest, with one finger poised as if in mid-explanation. It is a gesture that suggests thought in action—perhaps an idea being formed or a truth being shared. It is through this small yet potent movement that Pampaloni brings Leonardo to life, reminding viewers that this was a man always in motion, intellectually if not always physically. This quiet dynamism is what gives the statue its depth and resonance. It does not attempt to overwhelm with grandeur; rather, it draws the viewer into a private moment of reflection, as if Leonardo is standing at the threshold between thought and revelation.

Florence was Leonardo’s formative city. Though born in Vinci, a small Tuscan town, he came to Florence in his teenage years to apprentice under Andrea del Verrocchio. It was in Verrocchio’s studio that he first developed the skills that would eventually lead him to become a master painter, sculptor, engineer, and scientist. During his time in Florence, Leonardo painted some of his earliest masterpieces and began the experiments that would mark him as a true innovator. The city’s vibrant intellectual environment, its access to classical texts, its patronage system, and its atmosphere of exploration all contributed to shaping the young da Vinci.

In this context, the decision to place Leonardo’s statue among the Uffizi’s arcades is deeply symbolic. The Uffizi itself, originally constructed by Giorgio Vasari for Cosimo I de’ Medici, was a Renaissance administrative building that later became a repository for the Medici family’s extensive art collection. Today, it stands as one of the most visited museums in the world, housing some of the greatest works of Renaissance art. The placement of Leonardo’s statue at the very entrance, therefore, makes a powerful statement. It is as if Leonardo stands watch over the legacy he helped create, welcoming visitors to the artistic tradition he once advanced.

The statue also speaks to the 19th-century ideals of the time in which it was created. Italy, then in the process of unification, was seeking to reclaim and redefine its national identity. The emphasis on honoring great Tuscans was not just about celebrating the past, but about inspiring the present. Leonardo, more than any other historical figure, represented the unity of science and art, reason and imagination. In an age where Italy was fragmented politically but rich in cultural heritage, figures like Leonardo were seen as bridges between regional pride and national unity.

What makes the statue particularly engaging is that it does not rely on ostentatious display or elaborate symbolism. Instead, it operates through restraint, elegance, and clarity—qualities that Leonardo himself valued. In a way, it mirrors Leonardo’s own approach to design and drawing. His sketches, for example, often reveal as much in what they omit as in what they include. Pampaloni, perhaps understanding this aesthetic, created a sculpture that allows room for thought and interpretation. The figure is complete yet open-ended, suggestive rather than declarative, much like the man himself.

Over the years, the statue has become a focal point for tourists and scholars alike. Many stop to photograph it, some to sketch it, and others simply to contemplate its quiet presence. While the Uffizi’s interiors draw attention for their spectacular paintings and masterpieces, the exterior statues offer a more subdued, though no less significant, encounter with history. Standing before the statue, one is reminded that Leonardo was not a mythical being but a man who walked these streets, observed these skies, and wrestled with ideas that continue to shape our world today.

Leonardo da Vinci’s contributions were not confined to any one domain. His art, including works like the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, revolutionized portraiture and religious imagery. His anatomical drawings advanced the understanding of the human body far beyond his time. His notebooks contain designs for machines—some fantastical, others practical—that anticipated helicopters, tanks, and calculators. He was fascinated by water, flight, optics, and geology. For Leonardo, knowledge was a unified whole, and the pursuit of understanding was a sacred endeavor. The statue, in its silent dignity, encapsulates this vast intellectual landscape.

In the modern age, Leonardo is often cited as the prototype of the Renaissance Man—the individual who seeks to develop all aspects of the self, to master both technical skill and philosophical thought. His life encourages integration across disciplines, a model now echoed in modern educational philosophies like STEAM, which combines Science, Technology, Engineering, the Arts, and Mathematics. Thus, the statue does not merely commemorate a historical figure; it acts as an icon for future generations. It invites viewers not only to remember, but to emulate. To ask questions, to seek connections, and to believe that knowledge is boundless.

Today, as millions visit Florence every year, the statue of Leonardo da Vinci continues to watch over the Uffizi courtyard. It requires no words to speak to those who pass by. Its presence is enough—a sculpted soul, forever standing in the city where his journey began. It is not simply a work of art; it is a quiet manifesto, a stone-bound invitation to wonder and to think.

In this way, Luigi Pampaloni’s statue fulfills its purpose not just as a piece of public art, but as a vessel for remembrance, reflection, and inspiration. As long as it stands, it will remind the world of a man who saw farther, thought deeper, and created more beautifully than most who came before or after him. And in doing so, it ensures that Leonardo da Vinci remains not only a figure of the past but a constant presence in the evolving story of human achievement.